How to Make Your Officers Look Like Gods: what happens when you bring Gothic symbolic density to naval fiction

Naval fiction has given us competence. I want to give you apotheosis.

Patrick O’Brian and C.S. Forester wrote grounded historical naval fiction masterfully—tactics, seamanship, the strain of command rendered with precision and authenticity. They gave us captains as skilled professionals navigating real historical conflicts. Watch any adaptation of Hornblower and you’ll see the same approach: competent men doing difficult jobs with skill and courage.

I’m not writing that. I’m writing elegiac naval Gothic—secondary-world maritime horror where officers are intermediaries between their crews and a sentient, jealous ocean. Where the uniform isn’t costume, it’s theological argument. Where competence doesn’t just work, it borders on divine possession.

This isn’t better or worse than grounded historical naval fiction. It’s different aesthetic territory. The same way Warhammer 40,000 didn’t replace Star Trek but claimed adjacent space—Gothic grimdark in the void instead of optimistic exploration—I’m claiming the space for Gothic grimdark at sea.

And it requires different tools.

The Problem: Competence Treated as Mundane

Here’s what grounded naval fiction gives you when a captain might take the helm in a storm:

The description of wind velocity. Wave height. The physical strain on the wheel. Maybe the set of the captain’s jaw, the tension in his shoulders. The action of seamanship rendered with technical precision.

Here’s what it doesn’t give you: the transfiguration.

The moment when a man executing skills at the absolute peak of human capability stops looking human and starts looking like something the sea itself has touched. The crew’s response isn’t just respect for competence—it’s the paralysis of witnessing the numinous made flesh.

Naval fiction is afraid to go Gothic. I’m not.

Because here’s what Gothic understands that mundane competence porn doesn’t: the moment a human exceeds human limits, they become something else. And in a setting where the ocean is sentient and hungry, that transformation isn’t metaphor—it’s survival mechanism. Officers don’t just look divine in moments of crisis. They have to become vessels for something older and stranger, or the sea claims everyone.

Showing the Work: Competence as Religious Experience

Let me show you how this functions in prose.

This is Vance—a pragmatic, working-class First Lieutenant—recalling his captain during the storm. He’s being asked by a child to describe what happened, and this is what he remembers:

He saw Somerset at the wheel. Not the charming, rakish officer who smiled his way through every wardroom and tavern, but the other Somerset—the one Vance had glimpsed at the summit of that impossible wave. Eyes wide, feral, his shoulders straining against the fine turquoise wool of his coat, the white countershading along his inner sleeves and flanks stark against the bruised sky—wounds of pearlblood rendered divine.

He looked like a man the sea had claimed.

He looked like a god.

Notice what’s happening here:

The uniform is doing narrative work. The turquoise wool (muirrine—the sacred color). The white countershading (dolphin mimicry). The visual description isn’t decoration—it’s showing Vance’s psychological experience of witnessing divine competence.

“Wounds of pearlblood rendered divine”—this is the iridescence, the light-catching quality we designed into the fabric. It looks like wounds that bleed pearl-light because the uniform is designed to make you look like you’ve survived the abyss and returned luminous.

This is what grounded historical naval won’t give you. O’Brian describes the action with technical precision. I describe the transfiguration.

The moment when skill becomes something else. When a man doing his job crosses the threshold into numinous. When his crew stops seeing their captain and starts seeing an intermediary between them and the divine, terrible ocean.

Vance can’t articulate this. He’s a practical man. So he reduces it to the simplest possible statement: “The captain did what needed to be done.”

But the reader sees what Vance saw. The Gothic sublime. The horror and beauty of competence executed at a level that stops being human and starts being possession.

What Secondary Worlds Allow: Material Culture as Theology

In historical fiction, you’re bound by accuracy. Uniforms looked a certain way. Rank insignia followed regulations. You can describe them beautifully, but you can’t redesign them to encode your world’s cosmology.

In secondary-world fiction, you have a superpower: you can design material culture from scratch to reflect belief systems.

I’m not writing about the Royal Navy (though I was deeply inspired.) I’m writing about Arune—a maritime nation where the ocean is god, where dolphins are sacred messengers present in the founding of empires, where the depths have myths and those myths have teeth.

So I asked: what would a culture that worships the ocean actually wear?

Answer: They’d wear the ocean’s sacred animals on their bodies.

The Dolphin Principle: Sacred Biomimicry

Dolphins (relansheer), particularly white dolphins—the Sollurela—are sacred to Arune. They’re messengers between the surface world and the deep, blessed creatures that navigate both realms without being claimed by either. They represent everything Arune aspires to: grace, intelligence, mastery of the ocean without being mastered by it.

So Arunean naval officers wear dolphin countershading.

White inner sleeves. White along the flanks of the coat. The same protective coloration that makes dolphins nearly invisible in open water—light from below, dark from above.

This isn’t decoration. This is identification. Officers are claiming the status of the sacred animal. They’re marking themselves as blessed, as chosen, as operating under divine protection.

When a captain stands on deck in full dress uniform, the white countershading creates a visual echo of the creature Arune holds most sacred. The uniform is making a theological argument: this man speaks to the sea, and the sea recognizes him as kin.

Color as Spiritual Geography

But it’s not just what they wear—it’s what color it is.

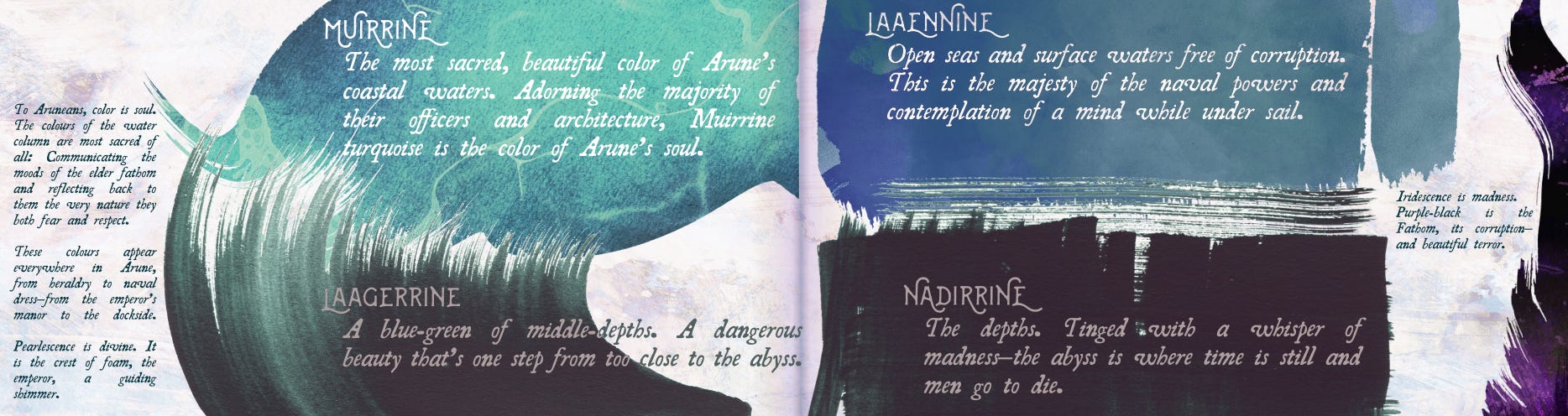

In Arune, color isn’t aesthetic preference. It’s spiritual geography. The water column—the vertical distance from surface to crushing depth—defines everything about their maritime culture. And that geography is encoded in color symbolism.

When an Arunean describes something as muirrine, they’re not just saying it’s blue. They’re saying it has the quality of the sea itself—sacred, beautiful, carrying the soul of their nation.

This is the innovation secondary-world fiction allows: systematic color symbolism that readers absorb through repetition, not explanation. You never have to stop and define these terms. Context does the work. The colors become a vocabulary for emotional and spiritual states.

Rank Insignia as Mythology: The Progression of Survival and Philosophy

Now we get to the shoulderboards. The rank insignia that every naval story includes but rarely makes mean anything beyond hierarchy.

I wanted rank to tell a story about what you’ve survived to earn it.

Lieutenant (Muiradon) : Churning, swirling waves on their insignia

Still learning to read the sea

Surface turbulence, chaos, motion

You command the waves, but the waves command you back

Captain (Maarendar) : The drauhessa appears

The drown-horse, the mythological mount of drowned sailors

Folkloric, cursed, the creature that claims those the sea takes

You’ve gone deep enough to encounter what lives in the myths

You’ve survived touching the cursed and returned to tell of it

At this rank, you don’t choose the drauhessa. It chooses you.

You’re a sea officer; you’ve been called to the deep. The insignia marks you as touched by the myth.

Commodore (Venmaarendar) : The relansheer (dolphin)

Administrative officers, shore command

They’ve chosen safety, chosen the blessed over the cursed

The dolphin says: I survived the deep, and I’m not going back

This is the path most officers take—up and away from the water

By commodore rank, many officers have moved to administrative roles. They’ve survived, and they’re choosing safety

The Dolphin Choice: Living or Skeletal

Any officer who wears the relansheer—commodore or admiral—faces an additional choice in how that dolphin is rendered:

The living relansheer—graceful, leaping, full of movement—honors the blessing itself. It emphasizes protection, the dolphin as sacred guardian, the forward-looking hope that the blessing will continue. Officers who wear this are choosing to focus on what the dolphin saves.

The skeletal relansheer—bleached white, stripped to bone—honors the dead. It acknowledges that the dolphin’s blessing didn’t save everyone. That you’re standing here because others aren’t. Officers who wear this are choosing to remember what the blessing cost.

Both are choosing safety. But one looks forward with faith, and one looks back with memory.

Admiral (Draumeir) : The choice

At this rank, you decide: dolphin or drauhessa?

Most choose the relansheer (dolphin) with pearlescent backing—pearl-light, the only illumination that returns from crush-depth

They’ve earned administrative safety—they take it

They’ve been to the abyss and returned luminous, and now they command from shore, from safety, from the blessed side of the myth

But some admirals keep the drauhessa.

And when you see that—when you see an admiral of the fleet wearing the drown-horse instead of the sacred dolphin—you know something about that man’s soul.

He’s chosen the call over safety. He’s chosen to remain a sea officer even when he could command from land. The drauhessa on his shoulder says: the ocean still speaks to me, and I still answer.

It’s fatalism made visible. The mythology teaches that the drauhessa appears to claim sailors, to carry them down to the drowning-places. Captains wear it because they’ve been called, touched by that myth, and they know—somewhere deep—that the sea will probably take them eventually.

Most men, reaching flag rank, choose to escape that fate. They’ve survived long enough. They take the dolphin, the blessed symbol, the promise of safety.

The ones who don’t? The admirals who still wear the cursed mount?

Those are the ones you watch. The ones the sea won’t let go of. The ones who won’t let go of the sea.

The Drauhessa: Dual Sacred Symbols

The drauhessa deserves special attention. In Arunean mythology, it’s not just “a sea horse”—it’s the mount of the drowned, the creature that appears when the sea claims a soul. It’s featured on heraldry alongside the white dolphin because both are sacred, but they represent opposite relationships with the ocean:

White Dolphin (Sollurela): Blessed, messenger, chosen by the sea, operates in the light

Drauhessa: Cursed, taker of souls, claimed by the abyss, dwells in the dark

Why do captains and admirals wear the symbol of the cursed alongside the blessed? Because to command at that level, you’ve been both chosen and claimed. The sea has touched you, marked you, and you survived. The drauhessa on your shoulder says: I’ve gone into the deep places where men die, and I came back.

The mythology teaches that the drauhessa appears to claim sailors, to carry them down to the drowning-places. Captains wear it because they’ve been called, touched by that myth, and they know—somewhere deep—that the sea will probably take them eventually.

And the pearlescent backing on admiral insignia? That iridescence, that play of light that shifts between soft pink, teal and orange depending on angle? That’s the only light that returns from crush-depth. Pearl-light. The organic treasure that forms in darkness under pressure.

You’ve been to the abyss. You brought back illumination.

Material as Message: The Pearlescent Detail

There’s one more detail worth noting: admiral-grade whites aren’t ordinary fabric. They’re woven to catch light with subtle pearlescence—soft pink and orange hues that appear only at certain angles. At a distance, an admiral looks militarily precise. Up close, the fabric breathes light.

This is intentional. Divinity should reward close observation. The mark of rank that doesn’t announce itself but reveals itself to those who’ve earned the right to stand that close.

(The distinction between pearlescence and iridescence in Arunean culture—one marking divine survival, the other marking fathom corruption—is its own essay. Another time.)

The Craft Principle: Make Material Culture Systematic

Here’s what I want you to take away from this:

If you’re building secondary worlds, your material culture should encode your themes systematically.

Don’t just tell your readers “the sea is sacred”—put the sacred sea on your characters’ bodies and make it mean something at every level:

Color: Not just pretty, but spiritual geography. Every shade tells you something about depth, danger, divinity.

Insignia: Not just rank markers, but mythology. What did you survive to earn this? What claimed you and let you go?

Cut and Construction: The uniform should communicate values. Arunean officers wear dolphin countershading because they claim blessed status. The coat’s lines matter. The way it moves in wind matters.

Material Quality: The iridescence of admiral whites isn’t showing off wealth—it’s showing survival. You’ve been to pressure that creates pearl-light.

This is worldbuilding through material culture. It’s what Gothic fiction has always done—every detail is symbolic, every object carries meaning, surface appearance and intimate reality are different things.

I’m bringing that symbolic density to naval fiction.

The genre has given us technical precision and historical authenticity. Beautiful. Necessary. I love it. But there’s room for something else—room for the Gothic sublime, for competence treated as apotheosis, for officers who look like what they actually are in moments of crisis: men communing with something vast and terrible that sometimes, horribly, answers.

Claiming New Territory

Elegiac naval Gothic is what happens when you take the competence and seamanship of historical naval fiction and admit what it actually feels like when executed at that level.

The sea is a jealous lover. Officers are her priests. The uniform is sacred vestment encoding a cosmology of depth, darkness, and divine blessing bought at terrible cost.

And when a captain takes the helm in a storm and brings his ship through the impossible, his crew isn’t watching a skilled professional—they’re watching transfiguration. A man becoming the conduit between them and the deep. A moment of competence so pure it borders on possession.

That’s the aesthetic territory I’m claiming. That’s what bringing Gothic symbolic density to naval fiction looks like.

Grounded historical naval fiction will always have its place—O’Brian and Forester built something beautiful and true. But there’s room beside it for something that admits the ocean is older and stranger than any history, that competence at its peak looks like divinity, that the uniform isn’t just clothing—it’s theology made visible.

Welcome to elegiac naval Gothic. The water’s dark, the officers are gods, and their dress whites bleed pearl-light.

And when they take the helm in a storm, they’re not performing seamanship—they’re performing transfiguration. That’s the aesthetic space I’m claiming. That’s elegiac naval Gothic.

If you’re curious about the actual maritime horror novel I’m building this aesthetic for, that’s The Reply—currently in development, set in the world of Nhera where the ocean is sentient, jealous, and only sometimes pretends to sleep.

If you want more craft breakdowns, character deep-dives, and worldbuilding analysis, subscribe. I post every Tuesday.

Fair winds,

—D. S. Black