Thunder and the Void

Designing Saren von Aurastor, or: how to build a storm that's terrified of stillness

Note: All characters, narratives, and artwork featured in this series are original works created as part of my portfolio development. These materials have not been published and are intended to demonstrate craft technique and understanding of the Warhammer 40,000 universe.

If Origen Thule is the crushing pressure of the deep ocean, Saren von Aurastor is the storm that screams across its surface—all thunder, lightning, and the desperate, magnificent performance of a man who cannot afford to stop moving.

Last time, I wrote about designing an antagonist whose power comes from Byronic stillness, from patient, ancient intelligence. Today, I want to dissect his perfect opposite: a character whose intensity comes from constant motion, whose control is maintained through perpetual performance, and whose greatest fear is the moment the theater goes dark and he’s forced to face what’s underneath.

This is about building a force of nature who is simultaneously apex predator and terrified child, wrapped in gilt and fury.

The Dossier: What You See

NAME: Lord Captain Saren von Aurastor

TITLE: Rogue Trader, Last Scion of House Aurastor

VESSEL: Novacula Mortis (Avenger-class Grand Cruiser, 7.5km, 141,000 souls)

KNOWN FOR: Ruthless efficiency, calculated charm, spectacular displays of authority, an overcoat that commands rooms

OFFICIAL RECORD: A man of refined cruelty and cold logic. Abhors emotional decision-making. Views people as assets to be collected and managed. Operates with brutal pragmatism in service to his Warrant of Trade.

THE TRUTH: Every single aspect of that performance is a defense mechanism against the void inside him.

Saren von Aurastor has no childhood memories. Decades ago, his family’s vessel—the Astrum Perdita—suffered a catastrophic Gellar Field failure during warp transit. The archaeotech aboard destabilized the ship’s warp translation, and the Immaterium tore through. When Arch-Inquisitor Origen Thule arrived to investigate, he found a lone survivor: a young man clutching xenotech fragments, his mind wiped clean by warp-exposure and trauma, surrounded by the wreckage of his entire dynasty.

What Origen saw was opportunity.

The Inquisitor struck a bargain: the archaeotech and all future finds in exchange for a new Warrant of Trade and the resources to reclaim power. Origen would forge this broken survivor into a tool—a deniable asset who could probe dangerous frontiers and acquire xenos artifacts that official channels could never touch. The ship that would become the Novacula Mortis was built from this devil’s bargain: salvaged components of the Astrum Perdita merged with a Grand Cruiser hull Origen had access to through his work with the Ordo Originatus.

Saren took the deal. Because the alternative—remaining powerless, remaining the terrified amnesiac—was unthinkable.

Everything he is now—the theater, the control, the possessive fury—is built on that absence. He is a man constructed entirely from scar tissue across decades of forcing himself to be undeniable. He can never, ever stop moving because stillness means confronting the hollow space where his foundation should be.

The Craft Concept: Designing the Beautiful Disaster

Motion as Survival

Where Origen’s design philosophy was “stillness as power,” Saren is built around the opposite principle: motion as survival. He is a performance that cannot end, a mask that has fused with the face beneath.

Every gesture is theatrical. Every word is calibrated. The clicking of his bronze-heeled boots, the swirl of that magnificent overcoat, the way he circles rooms like a predator establishing territory—it’s all part of an exhausting, never-ending show designed to keep the galaxy (and himself) from seeing the void underneath.

This creates a fundamentally different kind of threat than Origen. Where Origen waits and everything falls into his orbit, Saren moves and forces the world to keep pace. He’s centrifugal force—flying apart at incredible speed, held together only by the velocity itself.

The Paradox of Control

The central contradiction in Saren’s design is this: he desperately needs control, but his methods are fundamentally chaotic.

He claims to abhor emotional decision-making, to favor cold logic and calculated strategy. But everything he does is driven by a terror so profound it dictates his every action. His “logic” is just fear with better vocabulary. His “control” is actually a constant, frantic attempt to prevent the universe from taking anything else from him.

This is why his possessiveness is so violent. He doesn’t love people—he collects them. Not out of affection, but because losing control of what he considers “his” would mean experiencing that original trauma all over again. Every crew member, every artifact, every ally is insurance against powerlessness.

The horror of Saren isn’t that he’s cruel. It’s that he’s convinced himself his cruelty is pragmatism, when really it’s just a traumatized boy screaming into the void and calling it strategy.

The Performance and the Performer

One of the most interesting design challenges with Saren was this question: Is there anything left under the performance, or has the performance consumed him entirely?

The answer I landed on: Both. Simultaneously.

Saren is Schrödinger’s authenticity. The theatrical persona is so complete, so practiced over centuries, that it is him now. But in rare, devastating moments—when someone like Calix looks at him and says “the storm you hold back must be immense”—the mask cracks, and you see the terrified amnesiac boy adrift in wreckage.

Those moments are violations for him. To be seen is to lose control. To be understood is to be vulnerable. And vulnerability, for Saren, is death.

Visual Storytelling: Designing Thunder and Gilt

Every visual choice for Saren was designed to communicate spectacle, authority, and fragile control barely maintained.

The Ship as Metaphor

Before we even discuss his physical design, we need to talk about the Novacula Mortis.

The ship embodies everything about Saren’s constructed identity. It’s an Avenger-class Grand Cruiser—7.5 kilometers of rare, elegant lethality that most Rogue Traders could never acquire. At 141,000 souls, it’s a statement: I am legitimate. I am powerful. I matter.

But here’s what makes it perfect: it’s built from the corpse of his family’s ship.

When Origen salvaged the Astrum Perdita, he didn’t just scrap it. He merged its components with a Grand Cruiser hull he had access to through the Ordo Originatus, creating something new from the wreckage. Saren literally commands a rebuilt monument to his trauma. He can’t let go, so instead he transformed his greatest loss into his greatest asset. Every day, he walks corridors that might contain bulkheads from the ship that killed his family—a family he can’t even remember.

It’s the perfect metaphor for his entire existence: something magnificent built on top of devastation, performing strength while standing on a foundation of absence.

And like the man himself, the ship has a critical vulnerability. Avenger-class cruisers lack prow weapons, leaving them exposed to frontal assault. Most captains would consider this a fatal flaw. Saren sees it as proof of his tactical brilliance—he’s so skilled he can compensate for what lesser commanders would never risk. The ship, like the man, is a beautiful razor dancing at the edge of its own destruction.

There’s one more detail that reveals everything: Saren’s obsession with Geller Field stability borders on pathological. He monitors field integrity constantly, runs triple-redundant systems, and has been known to abort warp jumps at the slightest fluctuation. His crew whispers that he’d rather drift through realspace for months than risk even a microsecond of field destabilization.

They don’t understand why.

He’ll never tell them that somewhere in the blank void where his memories should be, his body remembers the Astrum Perdita tearing itself apart. His mind doesn’t know what happened. But his nervous system does. And it will do anything to prevent that helplessness from happening again.

The Silhouette

That overcoat. Good god, that overcoat.

It’s a vast, gilt-red and black garment that flows to his calves, with heavy faulds that amplify his already formidable height. The skull motif epaulettes, the intricate aiguillette arrangement, the sheer weight of it—this is costume as armor, as declaration, as the physical manifestation of “I am too magnificent to be powerless.”

Where Origen’s severe greatcoat communicates containment, Saren’s is pure expansion. It takes up space. It commands attention. It performs even when he’s standing still.

The bronze heel-taps aren’t just aesthetic—they’re theatrical rhythm, a constant auditory reminder of his presence. Click. Click. Click. Every step is a pronouncement.

The Face

Saren’s beauty is unsettling. It’s the sharp, predatory elegance of a raptor—refined features that should be attractive but instead trigger some instinctive alarm in prey animals.

The mismatched eyes (one cold silver, one ghost-light blue) create asymmetry that’s slightly wrong, slightly off. They scan surroundings with “wild, deranged intensity” because he’s constantly assessing threats, constantly calculating his next move.

And then there’s the warp-scar—that brutal, jagged mark across his left brow and forehead. In a face of calculated elegance, it’s the one thing he can’t control, can’t perform away. It’s the physical evidence of the trauma that made him, and no amount of gilt can cover it.

The Contrast with Origen

Where Origen’s scars are subtle archives of survived horror, Saren’s is a jagged scream. Where Origen conceals his daemon-marks under high collars, Saren’s trauma is literally written across his face. Where Origen’s design communicates “I have processed and cataloged my pain,” Saren’s screams “I am running from mine at full speed and calling it confidence.”

This visual language tells you everything about their dynamic: Origen has made peace with his horrors. Saren is at war with his.

The Voice: Performance as Weapon

Saren’s dialogue is designed to be the opposite of Origen’s economical precision. Where Origen wastes nothing, Saren uses language as spectacle, as territory-marking, as constant proof of his magnificence.

Consider this exchange from a scene I’m working on, where Calix attempts to return a weapon Saren gave him:

“A fine weapon,” Saren murmured as he came to a halt before Calix, his mismatched eyes not on the pistol, but on Calix’s face. “A tool for a precise hand. It suits you. Keep it.”

“My new master provides his own tools, Lord Captain,” Calix replied.

The words seemed to absorb all sound in the cavernous room. The slow, rhythmic clicking of Saren’s boots ceased. He went utterly still, his head tilting fractionally, like a predator that has just caught an unexpected, dangerous scent on the wind.

“Your... master,” Saren repeated, the words a low, dangerous purr.

Watch what he does with language here:

The Setup: He’s being generous, paternal even—a performance of magnanimity that establishes his power through gift-giving.

The Disruption: Calix’s simple statement of fact (”my new master”) completely undermines the performance. Suddenly Saren isn’t the patron; he’s being rejected.

The Reaction: He doesn’t explode. He goes still—the most terrifying thing he can do, because it means the performance has stopped and something real is emerging.

The Repetition: “Your... master.“ He tastes the words like poison, turning them over, making them weapons.

This is Saren’s dialogue strategy: use language to control the room, to perform dominance, but when that fails, the mask cracks and you see the genuine threat underneath.

The Theatrical vs. The Real

Later in that same scene:

“Look at you,” Saren whispered, his voice a low, hypnotic thrum. “Dressed in his sober colors, reciting his cold logic. A fine performance.”

He calls Calix’s new allegiance a “performance” because everything is performance to Saren. He can’t conceive of genuine transformation because his entire existence is theater. When someone acts differently, they must be performing—because the alternative (that change is real, that people can choose to leave) is too threatening to his control.

But then Calix says something that destroys him:

“The storm you hold back must be immense.”

And Saren breaks. Just for a moment. The performance shatters and you see “not the Lord Captain, not the master of the Novacula Mortis, but the ghost from the wreckage.”

That’s the essence of his dialogue: it’s all spectacular armor, brilliantly maintained, until someone finds the exact right words to crack it. Then you see the terrified boy underneath, before the mask slams back into place “colder, more perfect, and infinitely more dangerous than before.”

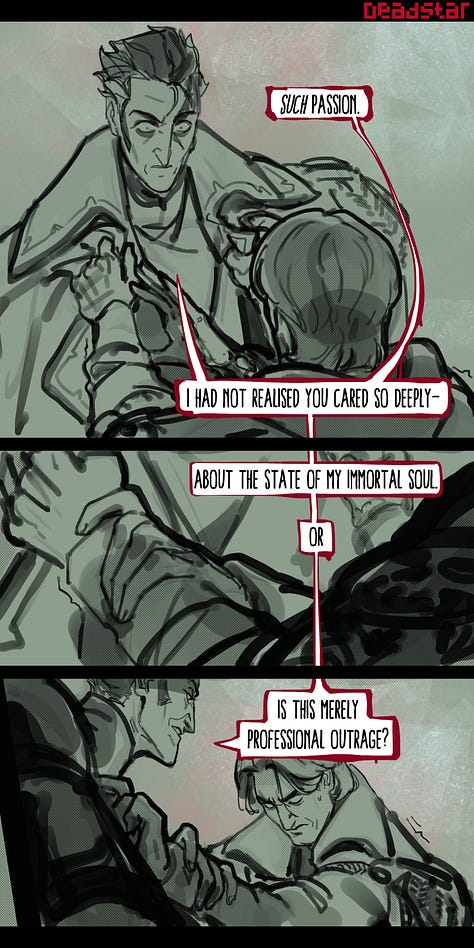

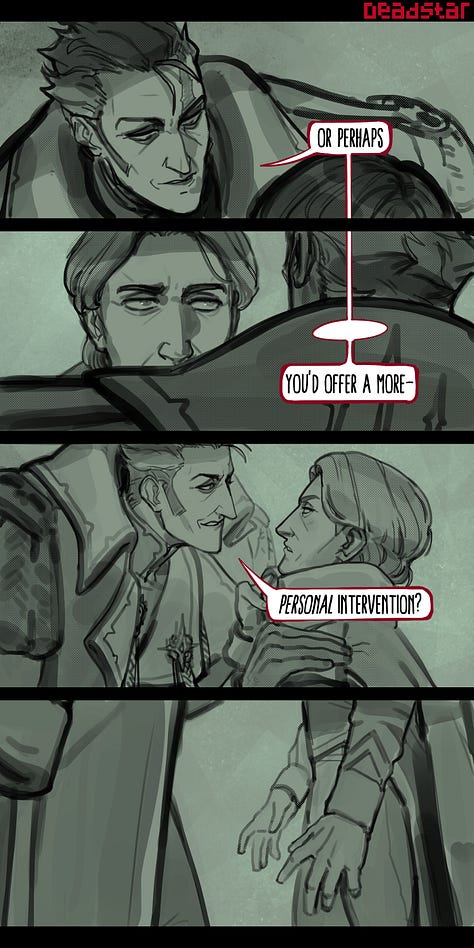

In this exchange, one of his retinue—an Inquisitorial agent assigned to his operation—confronts him about a dangerous decision. Watch Saren’s strategy:

Physical dominance - He uses proximity as a weapon, invading space, grabbing, looming

Theatrical dismissal - “How delightful. Your concern is noted.”

Reframing vulnerability as threat - He takes the subordinate’s genuine worry and turns it into something dangerous, something to be mocked

That last line is the key: “Your passionate sincerity is by far the most dangerous.”

Saren isn’t threatened by the accusation of courting damnation—he’s threatened by someone caring about whether he ruins himself. Genuine concern is terrifying because it requires acknowledging that he might be worth saving, that someone sees past the performance to the person underneath.

So he does what he always does: he weaponizes the intimacy, mocks the attachment, and reasserts control through cruelty. Because being seen is more frightening than any external threat.

This is the core of his character: he’ll use every tool at his disposal—physical intimidation, verbal brilliance, strategic cruelty—to ensure no one gets close enough to realize how hollow the foundation is.

The Dynamic: Creator and Creation, Storm and Singularity

Saren exists in perpetual tension with Origen because Origen is the one person who knows. Who found him in the wreckage. Who built him into what he is now. Who cannot be performed at, manipulated, or impressed because he’s seen Saren at his most powerless.

Origen represents:

The memory Saren doesn’t have

The parent he resents

The authority he cannot dismiss

The reminder of his constructed nature

Proof that his “control” was always an illusion

Saren represents:

Origen’s greatest success as a creator of assets

Proof that broken things can be reformed into weapons

The volatile, unpredictable result of cold methodology

Everything Origen is not: chaos, performance, emotional

Their scenes together are electric because Saren is desperate to prove he’s not Origen’s creation, while simultaneously needing Origen’s validation. He wants to be seen as an equal while knowing he was found as a powerless child. He performs magnificence while Origen sees through to the mechanism underneath.

When Origen says “Do not speak to me of darkness” and reveals his daemon scars, he doesn’t just win the argument—he unmakes Saren’s entire position. Saren’s swagger, his pride, his magnificent defiance, all of it collapses because Origen just proved he’s survived worse, longer, and with more purpose.

“Well,” Saren drawled, “How could one ever compete?”

That line—delivered with his attempt at casual dismissal—is actually total surrender. For a man whose existence is predicated on never showing weakness, that moment of utter defeat is devastating.

The Memory Problem: Building Character on Absence

Here’s what makes Saren unique as a character design challenge: he has no origin story. Not because I haven’t written one, but because he doesn’t remember it.

This creates fascinating opportunities:

The Blank Slate

Without memory, Saren has no anchor for his identity except what he’s built post-trauma. This means:

Every quirk is deliberately constructed

Every preference is a choice rather than inheritance

His entire personality is scar tissue—a structure built in response to wounding

The Gnawing Uncertainty

The absence of memory means he can never be sure:

If he’s “being himself” or performing what he thinks he should be

If his fear of loss is proportional or paranoid

If anything about his identity is “real”

This uncertainty is the static he’s constantly at war with. The performance can never stop because stopping means confronting the possibility that there’s nothing underneath.

The Collector’s Impulse

His obsessive need to collect and possess things makes perfect psychological sense: if you have no past, no memories to anchor your sense of self, then your identity becomes what you own. Every artifact, every subordinate, every piece of gilt becomes evidence that you exist, that you matter, that you have substance.

To lose something he owns isn’t just pragmatic failure—it’s existential threat.

The Romance of Ruin

If you were designing Saren as a romance option (à la a companion quest concept), the entire arc would be about whether genuine intimacy can exist when one person is incapable of vulnerability without self-destruction.

The “romance” would be:

A high-stakes game of intellectual chess

Constant testing and manipulation

Rare, shocking moments of accidental honesty that he immediately tries to retract

The slow, painful realization that being known might be worth the terror of being seen

The climax wouldn’t be a love confession. It would be Saren allowing someone to see him in stillness—not performing, not controlling, just being—and not immediately destroying that vulnerability with defensive cruelty.

That would be his ultimate character growth: learning that intimacy isn’t possession, and that being understood isn’t the same as being controlled.

But getting there would require someone willing to weather the storm long enough to find the eye of it.

Conclusion: The Architecture of Thunder

Creating Saren required building him in deliberate opposition to Origen while giving him his own internal logic:

Where Origen is patient, Saren is frantic

Where Origen processes, Saren performs

Where Origen waits, Saren moves

Where Origen has made peace with his trauma, Saren is still running from his

But both are survivors. Both are brilliant. Both are terrifying in their respective ways.

Saren is what happens when trauma isn’t processed but weaponized, when vulnerability is so unacceptable that you rebuild yourself as pure spectacle, when the performance becomes so complete that you can’t remember what you looked like before you put on the mask.

He’s magnificent. He’s dangerous. He’s exhausting. And somewhere under all that gilt and fury is a terrified boy who just wants to stop running but has forgotten how to stand still.

He is thunder trying to outrun the silence that will inevitably follow.

What are your favorite examples of “performative” characters in fiction—people who’ve become their masks? Which aspect of Saren’s design interests you most?

Next time: We’ll explore Calix von Fellner—the observer caught between these two crushing gravities, and what it means to be the prize in their game.